Online Feminism #Femfuture and the “Dirty” Money Problem

What is Feminism? We have tried to define this mysterious modern women’s affliction almost since the day the first woman came forward with her observation that “sh#t is unfair.”

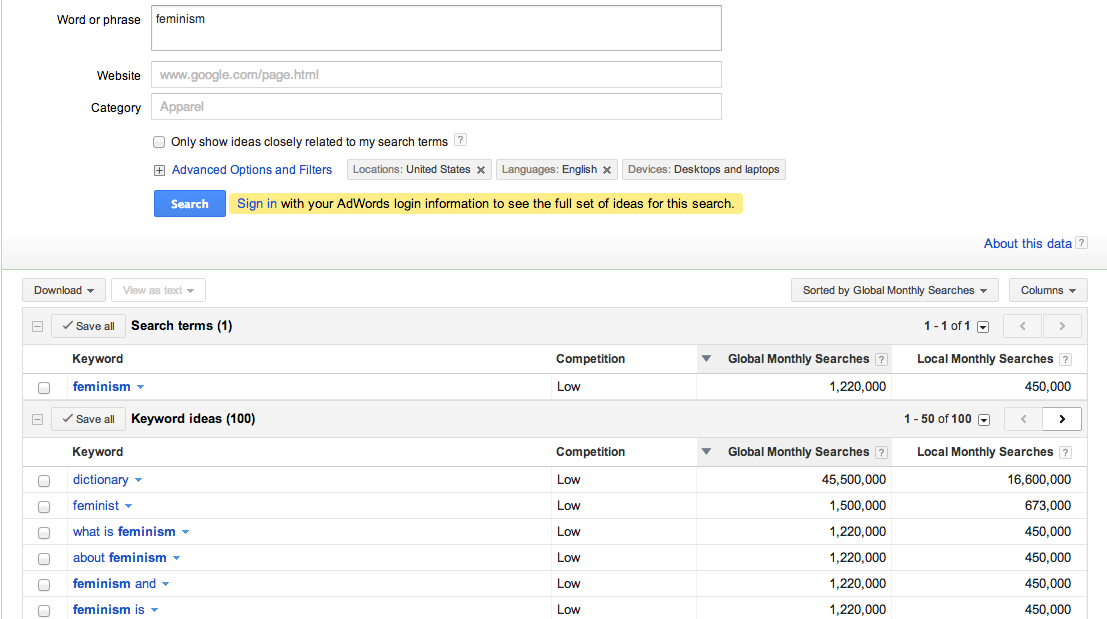

Many young women no longer call themselves feminists because the label is either too defined–bra burning hippie lesbians, or not defined enough—the most popular Google search relating to feminism is: “what is feminism,” garnering 1,220,000 hits globally per month.

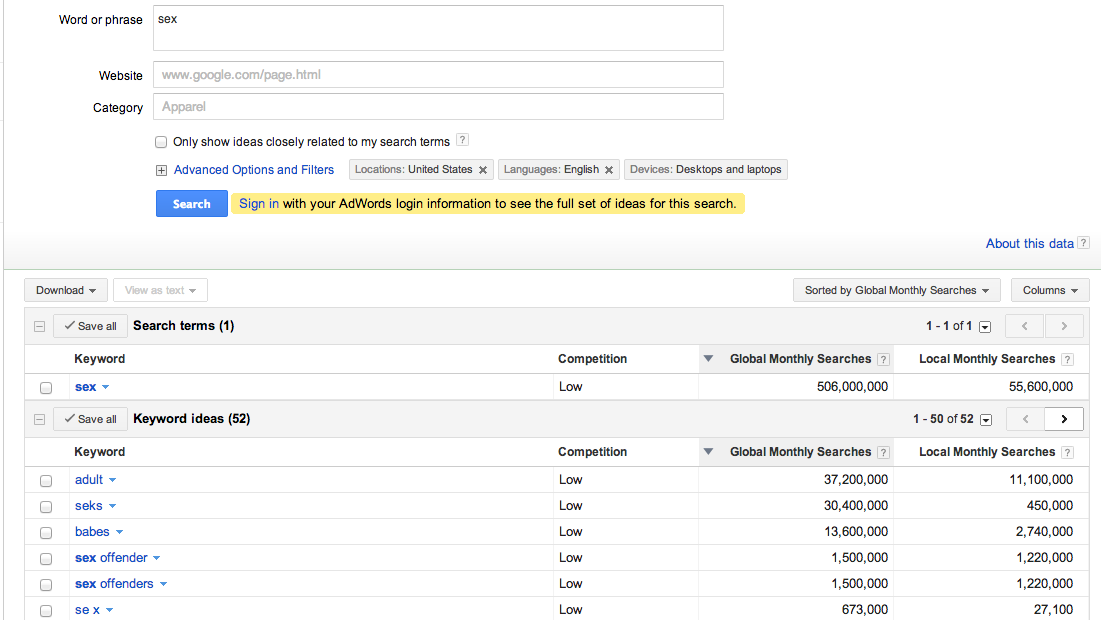

Notice how numbers compare with searches for “sex” below.

Other women cling to the term, certain that what they fight for and believe in is the quintessential definition of feminism, one they will defend doggedly and woe be it unto those who do things differently and dare to claim the moniker.

Then there are phenomenon a like “Girl Power,” the Spice Girls’ version of “feminism,” which in many ways served to undercut women’s struggles by branding, commodifying and selling them back to society in a packaged from, divorced in many ways from substance.

It’s so pretty and sparkly!

It is doubtful that the Spice Girls provided feminist epiphanies, but I can’t categorically say they didn’t. If their feminist struggle was to make as much money as boy bands, I can sympathize. If their struggle was to get along and respect each others ideas and contributions as a group of women, recent controversy over the “Future of Online Feminism” (#femfuture) report helps me sympathize here too.

The report was issued by Courtney Martin and Vanessa Valenti, women who strive to make a career in feminism. A career in feminism can mean many things, from the terrifying fluff of “girl power” to working at a domestic violence shelter or as an inspired politician. For Martin and Valenti, it means creating media. Martin has authored books and Valenti founded Feministing.com

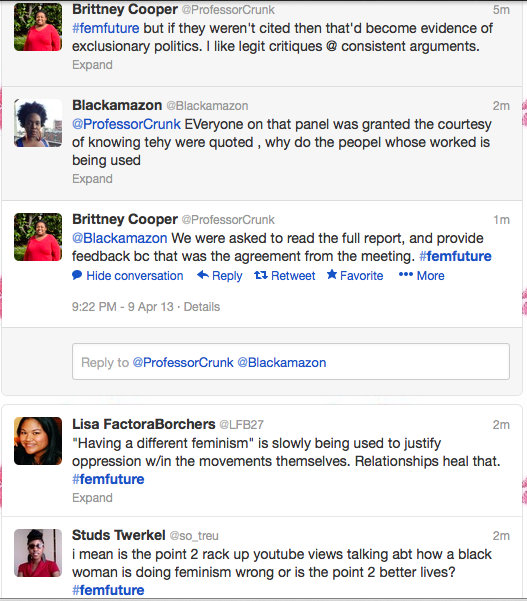

Much of the recent backlash surrounding Valenti and Martin’s report seems to stem from the fact that they didn’t include all feminist bloggers and from the idea that Valenti and Martin have the gall to think they should get paid for what others term “online activism.”

Brittney Cooper is founder of Crunkfeministcollective.com and a participant in the “Future of Online Feminism” report. Above, she engages with feminists who question the inclusivity of the report.

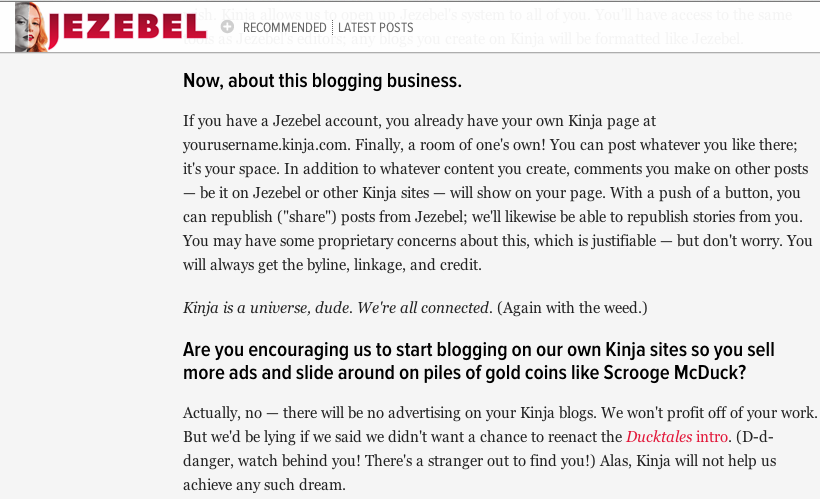

This critique comes as Jezebel, the for-profit feminist juggernaut rolled out a platform (very similar to Feministing’s) by which users may create their own content and have their own blog as part of Jezebel. But don’t worry, Jezebel says, ‘we’re not trying to make money off of you, just give us all your genius ideas.’ Who needs unpaid internships when we can all write for free for Jezebel for free?

But guess what, Jezebel’s definitely got me beat. Nearly 50 percent of “feminist” articles I come across through friends have the Jezebel brand attached to them. I’m not saying that all the content is original and theirs, but they have found a way (paying people!!) to amplify their influence.

This brings us to some intersectionality of a different kind. Discussion surrounding online feminism is not just about feminism, but also about women’s labor and the creative class, a group of people who add tremendous value to society, but often work without fair compensation. Money is the system we have here, money is how I buy my food. While capitalism is far from perfect and a product of the patriarchy, and while one wouldn’t want a big bank dictating how to run a feminist website, as one of my favorite bloggers (soon to publish a book) says, “bitches gotta eat.”

All those who work–whatever that work may be— should have the option of, or a pathway towards compensation. Content isn’t inherently free. Why should women, many of us already facing glass ceilings and pay disparities, also be told that our words hold no value, when statistics show that we own the Internet?

While the Internet has split open a chorus of voices, those who have time and energy to excercise their freedom of speech without compensation are a privileged few, those who gain traction even fewer.

With the rise of unpaid media internships, where college kids add value to already rich publications in exchange for a leg up, what becomes of the lone blogger who works nights and only finds time to pursue her true passion occasionally? What becomes of the trained writer who is forced to work for companies or publications that rarely focus on feminist issues? Worse yet, what becomes of the public, inhaling corporate dictated “girl power” by the gallon and rape culture by the mile? What happens as “thinspiration” becomes a mainstream word? I am not saying this *will* happen if feminist writers are not compensated, but that it has.

Economic disparities of the great recession have drawn clear lines between the haves and have-nots, and while grassroots online feminism has done something to mitigate the backlash against oppressed people which often occurs during times of economic downturn, think of how much more could have been done with funding. Maybe we can kickstart our way to a place in the sun like Amanda Palmer, but is that really sustainable for everyone? For people with friends who don’t have money to give? As Valenti and Martin write, “An unfunded movement further privileges the privileged.” What a funded movement may accomplish remains to be seen.

Maybe we can just be “weekend feminists” with day jobs managing other websites or driving taxis, but when writing about feminist issues is what we want to do for a living, why shouldn’t we be able to?

*This article was made possible by the generous sponsorship of jury duty.

This post really has me thinking…Thank you for posting it.

Especially on the unpaid labor steez.

!R

[...] but labor nonetheless. How can we better appreciate ways love-work ties into dense histories of uncompensated labor and unrequired love within communities of color, and is linked to the same moments that birthed [...]

[...] but labor nonetheless. How can we better appreciate ways love-work ties into dense histories of uncompensated labor and unrequired love within communities of color, and is linked to the same moments that birthed [...]