LGBT TV: What Queer representation means to me

For every new queer character appearing on a TV series, there is an article written about how groundbreaking their depiction is. For example: Santana on Glee is a lesbian, OMG the world is saved! Some journalist or other interviews the (often straight) actor or actress about the challenges of playing gay, and mainstream media ties up the story with a bow, presenting us with a giant leap for equality.

In stark contrast, a vast majority of queer counter-culture articles throw shade

hating on pretty much every single queer character, from the depiction to the actors, and throwing in–for good measure–the journalists who applaud those shows as well.

From vitriol of my youth levied at Will and Grace and Ellen, to present critiques of the prime time queer family sitcom The New Normal, it seems like queers just can’t stop crying out over minor stereotyping or sexlessness for long enough to actually catch a punchline, humor entirely opaqued by their self-righteous rage. Queer as Folk US was tooooo overtly sexual, the bodies toooooo traditionally beautiful, the lesbian characters were toooooo heternormative, more so even than those on The L Word. Evil, everywhere. It must be stopped!

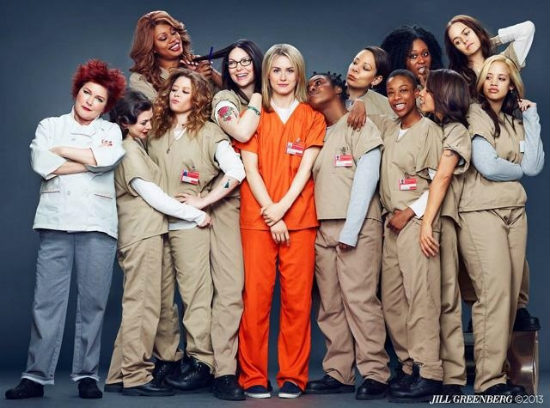

And let’s not forget the recent critiques levied at Orange is the New Black, a Netflix original series that features a three-dimensional minority transgendered character as well as numerous supporting characters who are queer women of color. A show based upon a memoir and directed by a real life lesbian (Jenji Kohan) and gaining massive popularity despite the fact that is not accessible without a Netflix subscription. And yeah, the show takes place in a prison, but it is fantastic.

Despite the growing popularity of queer characters, many radical queers want no part in mainstream media representation at all, viewing it as a straight-laced, undersexualized and bourgeois subterfuge: carrots on sticks. In Mattilda Sycamore’s queer anthology Why Are Faggots So Afraid of Faggots? one essayist writes that it was better when the fight for liberation was out in the streets, when no one accepted queers and things remained clandestine, but radical. Beautiful masochist sentiments like these are bred from a kind of common forgetfulness that I recognize in certain cultural critics and reactionary conservatives alike: that, in the words of old-timey genius and Spanish poet Jorge Manrique: “all past time was better.” Do people of color say the same about the happy time of segregation, when lynchings were all but legal, or women about the right to vote? I’m sure those struggles were just as titillating.

When I came out to my very straight cisgendered friend Keiko at the tender age of 20, she instantly said. “Oh, that’s cool. I really like Will & Grace!’” I did clear up that my life wasn’t much like that (at all, actually), but I offered that I also found the show hilarious. Should I have yelled in her face that those characters promoted a conservative, unrepresentative, gross misrepresentation of queer liberation? Perhaps. But instead, I accepted the show as her own personal stepping stone toward understanding queer relationality, and I kept my relationship with her as a means toward more open-minded socialization. I decided to do this not because I have low self esteem, or because I’m a preppy boring HRC gay, but because I had a deep respect for her individual intellectual and emotional trajectory.

We have seen a plethora of queer characters appear in the media in the decade and change since Will and Grace and Ellen came out of the closet on the small screen. Queers of color, trans characters and queer children have broken into the scene: Omar, the complex vigilante from The Wire and Lafayette the candid and caring diner cook from True Blood; Candice Cane’s brave and highly relatable Carmelita in Dirty Money and genderqueer character Max from The L Word; flamboyant young Hispanic teen Justin from Ugly Betty and lady-crazy, sharp-tongued Isabelle from Weeds. These characters literally popped into my mind right away; I didn’t even have to try very hard or google anything. No one will ever feel fully represented by images in the media, but we must admit, much to our radical chagrin, that as both bellwether and harbinger, the media has allowed for queer visibility to become more and more (the new normal) acceptable.

And what about questioning characters, like Tara from True Blood, who only began getting jiggy with ladies halfway through the show, or empty-eyed, bi-sexual Brittney and conniving queer Santana from Glee?

The first gay character on American television came into people’s homes in the 70s with the pioneering reality show, An American Family. Why then? It’s enough to look at Tom Bianchi’s recent photo book Tom Bianchi: Fire Island Pines, Polaroids 1975-1983, or remember Jill Johnston’s more radical Lesbian Nation, touchstones of the emerging queer scene of the 70s. Gays in the city had become increasingly visible and recognizable–although not yet fully integrated into the fabric of the American imago. As queers learned to recognize each other and formed small communities of melancholy memory, queer identity solidified into something both within and outside our control. The more “known” we are, the more misunderstood.

I have the distinct feeling that Lance Loud, the only out member of “An American Family” got called out by his fellows queers for being too nelly or too butch or too trendy way back then too.

Lance Loud at his best.

Certainly media representation remains and will forever remain incomplete. However, I find two aspects of mass culture to be particularly crucial to its social relevance: 1) its ability to reach millions, effectively reaching the potential for Zeitgeist alteration/creation 2) its role as a marker of changing media ideologies and circulating social tropes. To dismiss it entirely as either unrelated to the struggles of individual queers or as an ineffective tool of cultural persuasion would be reductive.

The thing about certain queer radicals is that often, they not only judge, but impose. They tell non-radicals how they must feel about things. You must be outraged, you must be discontent. I’m not big on tactics that focus on seeking out and unilaterally destroying ideologies. I am occasionally hard-pressed to find the difference between decolonization and its Other, when one group of people insists to another that no, wait, THIS is the right way to think and live.

I am not saying everyone should enjoy shows like The Fosters or Modern Family, both of which feature married gay partners and their interracial adoptive families, but here is my point: to deny their significance as indices of acceptance, to spit in such acceptance’s face, is to remain a navel-gazing critic, reducing “community” to the four other angry queers who clap and nod at our every self-righteous diatribe. No such show could or should claim to represent all queers always, nor that our struggles are over. But strides have been made and I believe we are headed, generally, in the right direction. Part of fighting for change means being anchored in the real and being aware of the impetus behind our criticism. Rather than incessantly decry all queer representation in the media as unified, pigeon-holding, concerted evil, why not re-appropriate these images, redistribute them, use them. Get people to watch them, find one that’s not so bad or make your own. Or put something out there yourself. Grassroots efforts, if that’s your bag (as it is mine), plant a seed, I’m all for it. Web shows like The Outs and Between Women have come up like shoots.

My favorite queer show? The Real L Word, hands down. And I can’t wait for the next season.

This post was written by an Ivy League graduate student who wishes to remain anonymous.